It was one or two summers ago that I finally saw the light. Mammy had been staying with us some since a stroke had virtually paralyzed her right side. Every year during the week preceding the fourth of July holiday, the Lafayette 9th Street Hill Historic Association held a "Festooned Fourth." During this week, red, white, and blue flags, banners, streamers, and bows draped the fences, yards, and porches of stately old mansions along 9th street hill. One hot Sunday afternoon after we went out to eat, I was determined to take Mammy on a walking tour of the hill. "Are you going to push that wheel chair up and down the hill in this heat," my husband Benny protested, "because I'm not!" He grudgingly parked the car at the bottom of the hill at my insistence. The air was hot and still as I pushed Mammy's wheelchair up the hill on the left side of the street. Even though Mammy only weighed a frail ninety pounds, I found myself huffing and puffing by the time we reached the top. As we headed back down the right side, the sidewalk was so uneven and the grade so steep that I had visions of the wheel chair either getting away from me and careening down the hill with Mammy in it or hitting a bump too hard and pitching Mammy out on the side walk. Benny just sat in the car and laughed at us. But what I remember most about this little excursion, is that more than the stately homes and colorful fabrics that we walked by, Mammy oohed and aahed over the flowers. "Those are purty," she said. "I just love fl'ars." Standing there, in the heat of the day and in the midst of all the grandeur of historic 9th street hill, I realized, yes, this woman really did love flowers.

Other than sharing the same birthday (we were both born on May 4), my Mother-In-Law and I didn't start out with much in common. I was born in 1950 to parents from two different parts of the country who had met in college after World War II. Dad was able to attend because of the GI bill. Some of my early memories were of living in married student housing at Indiana University where my parents were pursuing advanced degrees in geology and paleontology. Before coming to live with my maternal grandparents in 1963, after my parents' divorce, I grew up in a nuclear family that followed mining corporations around the country as well as in and out of it. An only child for fifteen years, I was not accustomed to sharing birthdays or much of anything else, and the only expectations my family had of me were to excel with books and to go to college. My adult years seemed to be spent pursuing a career in the computer field and, as an avocation, shopping for mutual funds.

Mammy, by contrast, was born in a dry county in Kentucky forty years earlier to the day. Because her parents James Daniel and Mary Pernetta were cousins, both their surnames were Couch. Mammy never lived off the property that had been in her family for many generations. The first Couch, also a James Daniel, journeyed from Virginia to Kentucky with a few slaves to purchase a thousand acres, which kept getting subdivided among each following generation. Mammy ended up owning forty some acres of the original farm and consequently lived out her life surrounded by cousins and life-long neighbors on all sides. Her older sister Mildred, better known as Sissy to the family or as Miss Mildred to almost everyone else, married and settled with her husband Carl on a farm a few miles down the same road closer to town.

Whenever I would listen to Mammy and my husband Benny converse during our many visits in each other's homes, it seemed to me that there wasn't a name in Webster Country - or at least in the Slaughters-Mount Pleasant or Gourd Neck-Shake Rag communities whose lineage Mammy couldn't trace. Not poor by the community's standards, Mammy's parents lived in a wood frame house built by the original James Daniel Couch. It had a screened in back porch, a sitting room or parlor, and several bedrooms, and fireplaces. Mammy's parents cooked on a coal stove or on the open fire, boiled water from the creek to do laundry, made their own lye soap, and even spun their own cloth. In Mammy's married years, she had electricity, but did not have indoor plumbing until 1968, the year I graduated from high school. At that time she and Cletus, my father-in-law (or Pappy as he was affectionately known), built a modest ranch-style home on the property. I was not to enter in to the scene for another twelve years. The old house sat behind the new home until the early 80's at which time, Benny's classmate, who happened to be a neighbor, bought the structure and incorporated it into a new home that he was building in his woods.

Far from growing up in a nuclear family, Mammy, her brother John, and Sissy lived with their parents and their "old-maid Aunt Sally" whom they all called "Cackie" or "Cack." An excellent cook and most particular in her housekeeping, Cack ruled the roost and was the model from whom Mammy derived most of her homemaking skills. The family raised a few cash crops such as tobacco, but mostly grew, raised, or made everything else they used, so there was no need to buy a lot of things. However, Mammy's parents did work on a road crew one year in the early nineteen hundreds in southern Indiana to earn some extra cash. During this entire period, they camped out at the construction site. Ruth's aunts and uncles lived all around them. An older cousin Franklin Winstead who loved to tease both Ruth and Sissy gave her the nickname "Bunch." Franklin wasn't the only one who liked to tease. One time, Mammy's parents left her and Sissy to finish up dishes after a meal. Instead of helping Sissy, Mammy lay down and took a nap. While she was sleeping, Sissy pulled together some clothes, stuffed them, and sat them up in a chair to look like a person. When Mammy woke up, she thought a stranger was sitting in her bedroom, and she ran screaming out the door.

Marriages between cousins were not uncommon at that time, and except for a tragic accident, there might have been another in the Couch family. There was a little cousin named Powhattan (pronounced Powtan) Winstead about five years old who doted on the young Ruth Couch. He so looked forward to starting school so that he could walk with "Ruf" and carry her lunch bucket for her.

One day he was playing happily on the front porch of the old Couch home where he was visiting "Ruf." He had a stick in his mouth. When he stepped off the far end of the porch, the stick accidentally penetrated the roof of his mouth. Almost 80 years later, Mammy vividly described the scene to us - how her mother grabbed the little fellow, who was bleeding profusely, up in her arms and ran with him almost a half a mile to her sister Hun's house, where he died shortly afterwards of internal bleeding.

Mammy went on to finish 10 grades of school. She boarded in Slaughters to take her secondary education. Not of a scholarly bent, she never cared much for Latin. Being with her friends at the boarding house was more fun than attending stuffy classes. Not that she skipped the latter, at least that we know of. As a young girl, she had to accompany Sissy to piano lessons which she found a bit tiresome. She did enjoy playing basketball and was a local track star. She won the county competition for her age bracket. Then, since Slaughters school didn't have anyone to compete in the next age bracket, they ran Mammy again and she won that race as well. So they sent her to the state competition in Louisville. Problem was here they made her wear track shoes! Mammy wasn’t used to running in shoes and it threw her speed.

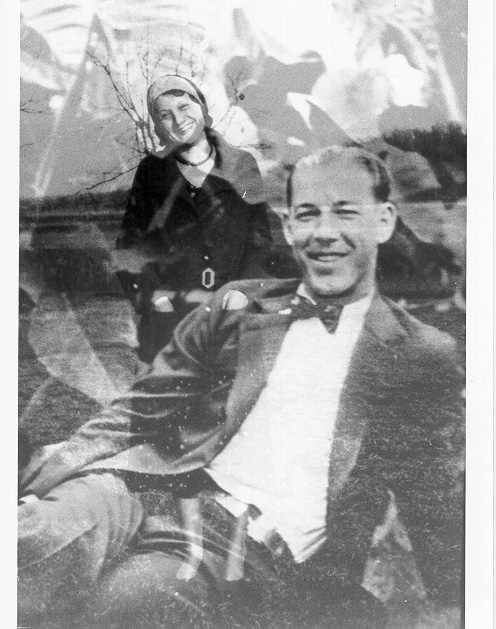

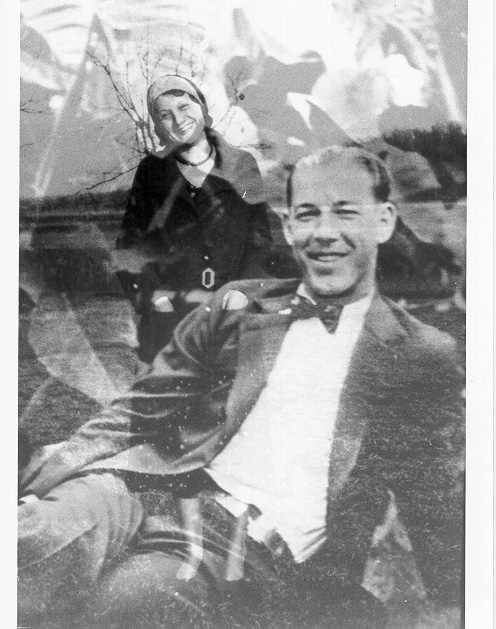

When she was a young woman, she met Cletus Winstead from the Vandersburg area. She and Cletus both happened to be with their respective set of friends in Slaughters on a Saturday afternoon. Each noticed the other and each asked their friends who the other was. Raised by Cack's fastidious standards, Mammy remembered thinking to herself that he was the neatest boy she had ever seen. Cletus, who was very particular about his clothes and appearance, and who was quite handsome in his youth, thought she was the neatest girl he'd ever seen.

After Ruth and Cletus married, her parents lived with them until their deaths. Ruth and Cletus had four children, Betty, Jenny, Paul, and my husband Benny. Sissy and Carl down the road had five children, Dorothy Mae, Harold, Jimmy, Charles Hayden, and Anna Laura. Cletus came from a family of twelve children and was very young when his mother died. His father did not remarry until some time later. Between the Winsteads and the Couch's, there were many, many aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews and cousins in the community who would all come to visit Cletus and Aunt Nettie and Uncle Jim, or Grandma and Grandpa, as the case may be. During these years, Mammy worked very hard providing for her family. A small woman, who probably weighed no more than 110 pounds in her life, she willingly carried buckets of water up hill to use for cooking and cleaning. Many times she, the girls, Sissy and even Grandma, when she was able, worked together canning wagon loads of corn that Benny and Paul would pick early in the morning, and bushels of green beans and peaches. Mammy's social life centered around the county extension Homemaker's club of which she was a charter member, her children's school activities, and the small Christian church that they all attended in Slaughters.

In 1956 James Daniel Couch, a three time Master of the local Masonic Lodge at Slaughters, died at home. The Old War Horse, ( or more accurately "Old Wah Hoss"), as he was fondly known, lay in state at home, and neighbors and family sat with the body in shifts through the night.

In his later years, "Old Wah Hoss" took nitroglycerin for a heart condition. The medicine made him hallucinate, a circumstance which provided no end of entertainment to the grand kids. One day when Paul, Benny, and Cletus came back from settin’ tobacco, they found Grandpa and Grandma Couch outside, in a state of panic about the big oak tree in the front yard.

"Get the cross ties! Brace that tree up, Cletus!" Grandpa hollered. "It’s falling over on the house!"

The tree was about thirty inches in diameter. Cletus grabbed the tree and pretended to straighten it up and set it down into the earth. That relieved Grandpa and Grandma.

A gold framed painting of the original James Daniel Couch hung in Grandma and Grandpa Couch’s bedroom. One day, while Benny was playing, Grandpa told him, "Take that hat off that man’s head in that picture."

Benny climbed up on a trunk, reached up to the painting, and pretended to take off the ancestor’s hat.

"Where do you want it, Grandpa - on the corner of this chair?" Benny pretended to hang it on Grandma’s rocker. Grandpa nodded, apparently satisfied.

Grandma Couch used snuff. She kept it in a can, with the lid slightly off. One day Grandpa Couch had a plate of eggs in front of him. Indicating Grandma’s can of snuff, he told Benny,"Pass me that shaker of salt."

Benny passed the snuff can to him and Grandpa shook it so hard over his eggs that Benny was afraid the lid would come off . But it didn’t.

When Grandpa Couch was a young man, he purchased a farm, but lost it due to a fondness he had for games of chance. Be that as it may, he was respected and well-liked in the community, known as "Mr. Couch." Cletus once said he never heard James say anything bad about anybody.

Grandpa Couch wasn’t supposed to have salt, but that didn’t stop him from asking for it. No one had the heart to tell him no, so Cousin Harold figured out how to put plastic wrap under the salt shaker. Grandpa would take that salt shaker, and shake and shake. "Don’t believe anything’s coming out," he’d say.

Grandpa Couch never had a car. On Saturday, Grandma would get him bathed and dressed, and he’d walk to town for the Lodge Meeting. Sometimes the Ritz brothers or Willie Pate would stop and give him a ride. Grandpa would hang around the Company Store or Harold’s gas station until the meeting started. Afterwards, everyone would go to Henderson (which wasn’t in a dry county) to get a few drinks. One particularly dark night after doing this, Grandpa walked home from Slaughters as usual. But when he reached the house, he couldn’t find the front door. He walked around the yard all night (or for at least two hours), striking matches to find his way.

Mary Pernetta Couch died at home in 1963 the same week that John Kennedy was assassinated. The family put her to rest with her Couch ancestors, a lineage who proudly claimed descent from Virginia Aristocracy, including one uncle who demanded to be buried upright and facing north, because he didn’t "want to turn his back on no damn yankees." He was interred at the Oddfellow cemetery in Madisonville. One by one Mammy and Cletus's children moved away, married, and started families of their own. Eventually they would all find their fame and fortune in Indiana. When Cletus died in 1983, nine months after falling off a tractor, Mammy, then 73, had never lived alone.

Always young in spirit, she mourned the prerequisite period of time, then suddenly announced she was taking a trip to Hawaii with her friends. It was probably her second time on an airplane. She and her friends, a circle of widow ladies in the community, formed a birthday club, went out to eat together and took trips. Once, someone from Lafayette, Indiana, who knew her children, recognized her at Opryland in Nashville. When he spoke to her, she promptly informed him that she was out spending her kids inheritance. She and Sissy talked almost everyday.

Mammy and Pappy were well into their retirement years when I came on the scene in 1981. Benny and I had met at a church singles group after his second divorce. Benny brought me home to meet the family the July 4th weekend when the tradition was to buy barbeque pork and mutton at Sebree Springs park. I suppose we got off to a respectable start under the circumstances. Disgruntled with his previous marital experiences, Benny had told his mother some time earlier that he was going to set his sights a little higher. When he brought me home, at five feet, ten inches, in my stocking feet, Mammy grinned at Benny. Holding up her hand, she said, "You sure did set your sights higher, didn't you?" For my part, I thought the terms "Mammy" and "Pappy" sounded too undignified, so I persisted in addressing Benny's folks as Ruth and Cletus for about two years. I noticed later that people in that community prefixed a Miss or Mr. before the first name when they addressed their elders. So a lilting "Miss Ruth" and "Mr. Cletus" would have sounded more musical or at least a little less blunt.

In 1991, shortly after her 80th birthday, a stroke left Mammy partially paralyzed on the right side. Once more, her life was to forever change. Very mindful that she had cared for her own parents in her home, the family was very uncomfortable with putting her into a nursing home. For her part, she did nothing to let them off the hook. She came to live with her children, mostly her daughter Jenny, and some with the rest of us. She was determined to regain the use of her right hand and foot and worked very hard at the exercises. Her one big hope was to be able to return home and live by herself and to drive again. When it became evident that some of the damage of the stroke was not reversible, Jenny and Jennifer advertised for a live-in caretaker so that she could return home to live. Sissy, who had written her faithfully during her absence, was glad to have her return and often stayed with her on Sundays. True to Cack's tradition, Mammy's standards in the cooking and cleaning departments were not satisfied by any one of a long string of caretakers that were in and out of her home over a two year period. She really looked forward to Benny's regular Sunday calls and among other subjects of interest, usually had a few criticisms about her housemate. Yet, she was content enough. Her friends and neighbors dropped by to see her, she and Sissy went to have their hair done every week at Madisonville, and when she felt like it, she and her caretaker participated in family and community social events.

Mammy's final days were characterized by the drama and humor that happens when a large group of people try to come together. The beginning of the end came on Memorial Day weekend 1994. Mammy woke up around 2:30 in the morning with breathing difficulties. In the rush to the hospital, her daughters Jenny and Betty ended up locking Mammy and the keys in the van at the Emergency Room entrance. Poor Mammy had to open the doors herself to get out. The doctors diagnosed her with congestive heart failure and put her on oxygen and diuretics. Benny and I came down that same weekend I remember we slept in a different bedroom than usual. After waking up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom, I stumbled back to bed half asleep, and totally disoriented. The room was pitch black. Istarted feeling my way around the bed, I ran my hand over Benny's soft, smooth hair, moved around the foot of the bed to the other side, and started to crawl in. Then a voice said, "Jeanne. This is Tootsie. You’re in the wrong room!"

"Oh, God, you guys, I'm so sorry!"

Absolutely mortified, I made my way back to our bedroom and told Benny I'd just tried to climb in bed with Tootsie and Jenny. Benny took this news well. All he said was, "Shee-it." We both lay in bed trying not to laugh too loudly for the next fifteen minutes.

The next morning, little Joseph asked, "Papaw, who was that lady touching my hair last night?"

I thought Benny's head had felt unusually small! Turns out Joseph was sleeping with his Grandpa Tootsie, while Jenny spent the night with grandaughter Jessica.

Mammy laughed when she heard about it.

So did Jenny.

On Sunday the hospital released Mammy to Senior Citizen's nursing home in nearby Madisonville. When she became too weak to come to the phone at the nursing home, Benny began to send her letters which I typed on the computer and into which I slipped photographs of our flowers. She seemed to enjoy these.

Just a month later Mammy's family took her out of the nursing home so that she could spend the July fourth weekend at home. Her weight had dropped to eighty-four pounds, but her alertness and sense of humor remained intact. Noticing that Tootsie was staying at his mother's place instead of at the house with Jenny, Mammy started laughing. "Tootsie's not here," she said. "He's probably afraid Jeanne's going to try to climb in bed with him." By Sunday when she returned to the nursing home, she was extremely weak. Just two weeks later, on Saturday, July 16th, at the insistence of granddaughter Jennifer, who was an RN, Mammy was admitted back into the hospital for breathing difficulty. That evening Mammy told Jenny and Jennifer that she was ready to die and that she wanted to go home to die. Monday June 18th, doctors performed a surgical procedure to withdraw fluid from her lungs with a needle. The procedure combined with morphine made Mammy more comfortable. Monday morning I took our suits to the cleaners and asked if they could have them ready for me that same day. On Tuesday morning, the doctor called to say that her right lung had collapsed. Jenny called Benny at work. He came home, threw a few things together and drove down to Kentucky. Mammy passed away at 10:35am. Her sister Sissy, recently turned ninety, and her daughter Jenny were sitting with her at the time. Mammy weighed only sixty pounds when she died.

Paul's factory was on shutdown for two weeks, and he and his wife Betty had left on a motorcycle trip out west with Betty's cousin Steve Green and his wife. When Paul called Sunday night and heard of Mammy's failing condition, he said they would start home the next day. He requested that the family not bury Mammy until they were able to get there. Monday evening the family got a cryptic message through Steve's parents in Dayton, Indiana, that Paul, Betty, Steve, and his wife had indeed started back but had run into some difficulties. No one knew their exact whereabouts or how to get in touch with them. Jenny, Betty, and Benny were on pins and needles. At the urging of the funeral director, they set the viewing for Thursday at 4p, and the funeral for Friday at 2p. Betty's husband Hal Ray called the State Police and had them start searching for Paul in Colorado and Wyoming. Early Wednesday evening Paul's son Bradley called to say Nettie, his sister, named for Mary Pernetta, was flying in from Arizona. He would be picking her up at the Indianapolis airport, and the two of them would drive down for the viewing. They still hadn't heard any news of their dad and mom's whereabouts. Finally late Wednesday evening, Paul called to say that he and Betty had been in a motorcycle accident Monday morning just outside of Yellowstone National Park. Paul had a hole in his ankle, a sprain, and cracked ribs. Betty had a badly bruised arm and cracked ribs. After getting out of the hospital, they had rented a truck to haul the motorcycles, and had continued their journey home with Steve Green doing the driving. They were now in Illinois. The family informed him of Mammy's passing and he said they would drive on to Lafayette and try to be in Kentucky for the viewing the next day.

All week long, I noticed that the weather itself seemed to be putting on a final show as Ruth's spirit took wing. While hot and progressively more humid, the days were sunny, and the sky blue and billowy with clouds. On the morning of the viewing Jenny went to the funeral home to put on Mammy's makeup. The viewing was held at Townsend's in Dixon, Kentucky. The funeral director requested that family arrive for the viewing before 3:30p. Six of us were there. When we walked in, we were amazed at all the flowers. Mammy lay in state surrounded by flowers - carnations, roses, day lillies, baby's breath, snapdragons, mums, gladiolas daisies, and exotic varieties in blues, violets, lilacs, oranges, melons, whites, reds, pinks, and yellows. It was as if the flowers themselves had sent representatives, no, delegations, to say their good-byes to her. Everyone who had known Mammy or known of her seemed to know of her love for flowers because flowers in arrangements, planters, and hanging baskets were spread along either side of the casket, at the back of the room, and extended into three other rooms. As neighbors, cousins, nieces, nephews, grandchildren and great grandchildren started to arrive, Benny said, "If Mammy could just see all of this - the flowers and all the attention, she'd say, 'This was worth dying for.'"

In the faces of Pappy's nephews and nieces, the Winstead features gave me the sense that Pappy himself had come back, traveling across an eleven year time span since his death, to attend Ruth's viewing. Relief and emotions ran high when Paul came hobbling in with his son Bradley and stood weeping in front of the casket joined by his brother and sisters.

The funeral service was held at Slaughters Christian Church with a viewing before the funeral from 12:00pm to 2:00pm. The small congregation, probably less than thirty people, had recently made improvements to the 125 year old building. They had covered the hard wood floors with a red carpet, replaced the good shepherd picture hanging behind the pulpit with a large plain wooden cross, put up ceiling fans, and painted and wallpapered the Sunday school rooms and bathrooms. In this smaller, more quaint setting where my husband had attended church as a child and where his grade school teacher Miss Ruth Nance was also his Sunday School teacher, the presence of the flowers was even more bold. Paul counted 63 bouquets. As we sat in the front pew in front of Ruth's casket, we seemed to be surrounded in a sea of flowers. Miss Ruth Nance albeit very aged was in attendance on this day. I sat down behind Sissy for a while and asked about Mammy's final hours. "She didn't know," said Sissy. "I saw her swallow twice right here." She touched her throat muscle. "She went real easy, just seemed to drift away."

"Is that the first time you've sat with someone like that?" I asked her. She shook her head, "I've seen lots of people die. But most go like this..." She breathed heavy a couple of times to illustrate labored breathing, then said, "Ruth didn't do that, she went easy."

The service was officiated by two ministers of the Christian Church, the Reverend Gary Ashby who was the current pastor and the Reverend Roland Ledbetter, a former pastor who had officiated Pappy's funeral. It was short and simple. Benny's classmate Janet Watson sang "In the garden." At the graveside service which followed, I could hear a single bird singing as the ministers gave their final messages. Just a stone’s throw away from Mammy’s and Pappy’s gravesite stood a small child’s grave marker. On it, in eroding letters, was engraved the name Powhattan Winstead, born June 1910, died April 1915. Mammy’s marker read Ruth Winstead, born May 1910, the ending date, July 1994 yet to be added.

Afterwards, the ladies and men of the congregation served a ham bake dinner for the family. Along with the ham, and other delicious food, there were fresh garden tomatoes and a jar of homemade sweet pickles.

Shortly after Mammy's death, the family closed up the small house outside of Slaughters, thus ending a thirteen year era of my visiting in that home. Mammy was one of those rare people in our lives who had nothing better to do than to spend time with us, and who appreciated simple things like watching the preparation of a daily meal. From my years of acquaintance with her, I carry with me a jam cake recipe passed down through her "old-maid" Aunt Cackie, as well as many images and memories, two of which stand out at this time. One is of Mammy's sister Sissy at the funeral home. Sissy, now ninety, had lived to bury her parents, her brother, her husband, two of her own children, and two great-grandchildren. When I greeted her, she took hold of my hand, shook her head, and said, "Oh, me...To give her up...Oh, me." The sorrow and desolation in her face throughout the two days of the viewing and funeral was an attestation that grief and heartache are no respecters of age.

The other image I carry with me is an admittedly whimsical one. It is a notion of the day that all the flowers decided to attend Mammy's funeral.

Postnote: Sissy was laid to rest in April of 1998, at 94 years of age, in the same cemetery, on a grassy knoll which overlooked the farmhouse where she and Carl and had lived and raised their family. A quiet person but an expressive writer, she was survived by one son, two daughters, eleven grandchildren, and twenty-two great-grandchildren.

|

|